Written by Denise Withers

When she was 11 years old, Christina Lamey got kicked out of minor hockey in Cape Breton. Not because she was violent, or lacked talent. Because she was a girl. And the league didn't know what to do with her.

"I lost everything that day. My identity. My friends. The game I'd been playing my whole life."

That experience lit a spark of anger that would smoulder for years before finally igniting a fire in her belly to change the game for girls in Nova Scotia for good.

"I realized what a sick scenario that was. Really, really bad. And so, there's no end to how much work I will put into this. Because I just saw it as so wrong, and until it's right, I won't quit."

Fast forward to 2015. Leijsa Wilton's 9-year-old daughter is one of two girls playing at a competitive level on a "mixed" team in the same region because there's nowhere else for her to go. Then, one day, someone tells her she shouldn't be there – that she's taking up a boy's spot.

"That was it for me," Leijsa recalls. "Who tells like a little kid something like that?"

That's how Christina and Leijsa came to be two of Nova Scotia's biggest champions for equal access to hockey for girls. Their goal was simple.

If you sign up for hockey, you should get to play. If it's any more complicated than that, you're screwing it up.

Although the issue of access is complex and influenced by culture, politics and finance, they've identified one core premise to use as a lever for change. If a rink is accessing public funds - and all rinks do at some point - then access to the rink must be equitable.

Using this as their focus, they've had incredible success over the last ten years.

Enough is enough

As the President of the women's hockey league in Halifax, Christina helped the sport grow from 8 to 28 teams in ten years. How? By finding a woman inside the municipal government who was sympathetic. The staffer took the issue to the City Council, which was shocked to discover the women were being shut out and implemented a community access policy for all publicly funded rinks. But the problem persisted elsewhere.

Years later, when she returned to Cape Breton, Christina took her daughter back to the rink she'd been kicked out of as a child, to sign her up for hockey. And she was horrified to see that nothing had changed. Not only were there few opportunities for girls, but boys were actually taking the puck away from girls on their own team during games. Only three girls' teams existed in the entire region – and all were run reluctantly by boys' leagues.

So she started a new team.

Meanwhile, Leijsa was doing the same thing for her daughter. Eventually, they broke free and became part of a standalone female hockey association, despite massive opposition and dirty tactics from the other minor hockey organizations that were afraid of losing control over the game.

By 2021, they'd proven that they could create and run effective programs so girls could play hockey at any level. But, it was still a struggle to get ice time. They were stuck.

That's when they discovered the Future of Hockey Lab – a six-month innovation program where they could join six other projects to find ways to shift the culture of hockey.

Designing a better future with the FHL

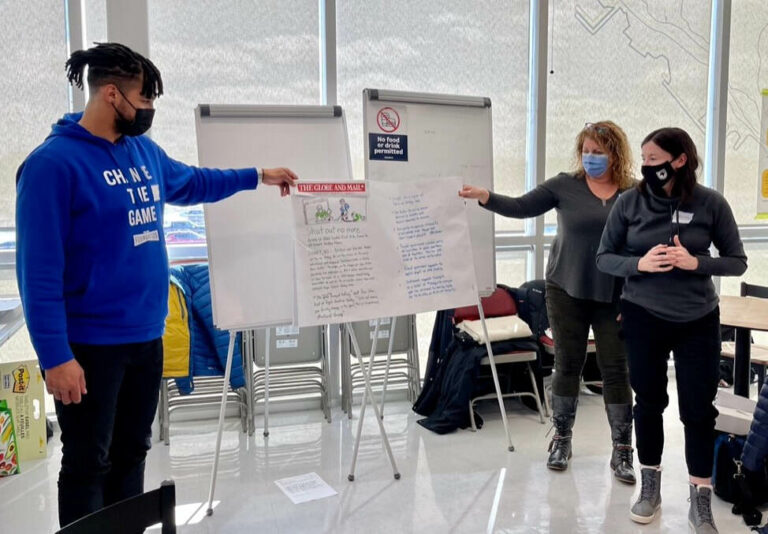

Their Lab journey started that fall at a two-day event that opened their eyes to both the scale of the problem they faced – and the opportunity to create collective impact.

Listening to the stories of the others, Leijsa and Christina realized that they all shared the same problem. Most of the other Lab participants represented groups who were also being systemically excluded from hockey and were trying to start new programs to make it more accessible. Yet, even if they could overcome barriers like equipment and registration, they would also need ice time.

The success of Christina and Leijsa's project, "No more leftovers", would be foundational to the success of the others.

With the support of their innovation coach, the pair worked through a series of creative and analytical activities to generate ideas about how best to move forward. Importantly, they also explored how to test their ideas - or prototype them - in a quick way that would allow them to learn what works without making big bets right upfront.

Based on their findings, they decided to build on Christina's success in Halifax and target their municipal government. It owned 3 of the 10 rinks in town, offering a total of 111 hours of prime ice time to local teams each week. Only 1 of those 111 hours went to girls hockey. Yet, the ratio of girls to boys playing was 1:3.

Even though they had the facts on their side, Christina and Leijsa knew it was going to be tough to shift this deeply entrenched practice of ice allocation on their own – to overcome issues of grandfathering, entitlement, discrimination and a scarcity mindset.

So, they used innovation tools like back-casting to come up with a multi-pronged approach. Essentially, they created a vision of their ideal future, then reverse-engineered it to identify key milestones they'd have to hit to be successful.

This helped them develop two additional plans.

Taking action for real system change

First, they decided to continue their strategy of making system change by focusing on public policy and took their fight to the province. Again, they reasoned that most rinks receive provincial funds at some point to operate and that no politician could make a case for continuing to restrict access to ice time to just support boys' hockey. Plus, it was becoming clear new rinks would need to be built, which would require provincial support.

Putting the onus on the province to lead change would also give local rink managers an "out" in future when they'd have to change the way they allocate ice, as they could always "blame it up".

Using the plans they developed in the Lab, they were able to find a supporter within the government who agreed to start the long process of creating a new policy.

At the same time, the pair also discovered a new opportunity – to refurbish a neglected rink at the local university and turn it into the future home of girls' hockey in the region. So they designed a campaign to win the funding they'd need from a national competition in the spring of 2022 called Kraft Hockeyville. Even if they didn't win, Christina and Leijsa were confident they'd be able to raise the money somehow.

Although they were farther ahead than other projects when they first came into the Lab, they still saw it have a real impact on their work.

Specifically, the Lab's processes, activities and facilitation gave them structure, focus and timelines – and helped make the pair's big ideas tangible with creative and analytical tools and processes. That made it easier for them to stay on track and meet their milestones.

Christina and Leijsa also found that the Lab's cohort approach created unexpected opportunities to scale and accelerate their work, by showing them how they could support other projects and tackle different parts of the same problem.

As Christina notes, that was one of the biggest benefits of joining the Lab. They were able to focus on creating systemic and structural change - not just temporary improvements, as had been the case historically.

We're on the verge of opening what might be Canada's first-ever home arena that is filled with girls’ hockey. And now you're getting into bricks and mortar. Allowing others who've been excluded from the sport to make their way into it successfully and permanently. That's what systemic change looks like.

Building momentum for the next generation

Still, there's much work to be done. This kind of change takes patience – something neither Christina nor Leijsa are good at. "Our innovation coach keeps telling us to be patient. But we just can't," Leijsa laughs. Christina chimes in, "Two things we've learned over the years to be successful are – never be patient and never ask permission."

In hindsight, she does acknowledge that it can be tough to see your progress when you're in the messy middle of this work. It's important to have a clear purpose that keeps you focused. For her, it's simple. If people sign up to play, they should be able to.

Luckily for girls' hockey, these two change-makers are in it for the long term. They're driven by a strong sense of social justice and anger at being shut out of the game for so much of their lives. With fire in their eyes, they challenge those who try to dismiss them. "Just tell us we can't do something, and we'll show you how fast we can do it better than you."

They also remind us that they're not just fighting for change for Cape Breton girls. They're fighting for the rights of all girls and women to access a game that offers incredible ROI in terms of physical, emotional and social benefits.

As Christina says, "Canada should be investing in arenas. We're a cold country with long winters. And hockey is the only sport you can play right into old age. Plus, it's one of the few sports with reliable, almost year-round access to facilities, unlike something like skiing that's weather dependent. I might get out to the ski hill five times a winter because of weather. But I can go to the rink any day of the week and I will get exercise. So dollar for dollar, the amount of use a community can get out of a rink is fantastic. Nine months of the year, pretty much every day of the week, 30 people on the ice, for 70 years of their life. The math of hockey is extraordinary. I would challenge any sport in the world to show math like that in Canada."

It's clear from the stories and work of the Lab that hockey is more than just a sport for Canadians. It's an identity.

Since creating and branding the new female hockey association in Cape Breton, Christina and Leijsa have seen a huge shift in uptake and attitudes toward girls' hockey. "The girls are just like, 'Wow. There's more of us than we thought!' Because they're no longer hidden in old jerseys handed down from the boys, settling for leftovers. They play for the Blizzard. They have their own identities."

It's also clear that they're passing along more than a love of the game. They're sharing their passion for change. When Leijsa finally got her daughter Leila onto a new, all-female team, they lost every game in their first year. Leila’s best friend left and went back to play for the boys. But her daughter stayed to help build the new team.

Wise beyond her 11 years, Leila told her mother, "If not me, then who? I have to stay for the girls coming behind."

These change-makers know that their Future of Hockey Lab project is just the beginning of a major culture shift in the game – one that's long overdue for Christina.

"This equity access policy on ice, it's just the next step to start to blow those doors open, to get girls feeling that hockey is for them. Hockey always was for them. In many ways, all of this effort is just taking something, steering it back to where it's supposed to be. And the Future of Hockey Lab is a great way to start to fix those things in the sport. Some people – they call this innovation. But to me, we're just fixing something that went wrong."